For decades, chronic ocular hypotony has sat in an uncomfortable clinical category: not quite an emergency, but often a slow march toward irreversible damage, poor vision, and eventual palliation. While acute postoperative hypotony can usually be corrected, the long-term, progressive form – driven by ciliary body failure and gradual loss of structural integrity – has historically left ophthalmologists with few meaningful options beyond observation or silicone oil.

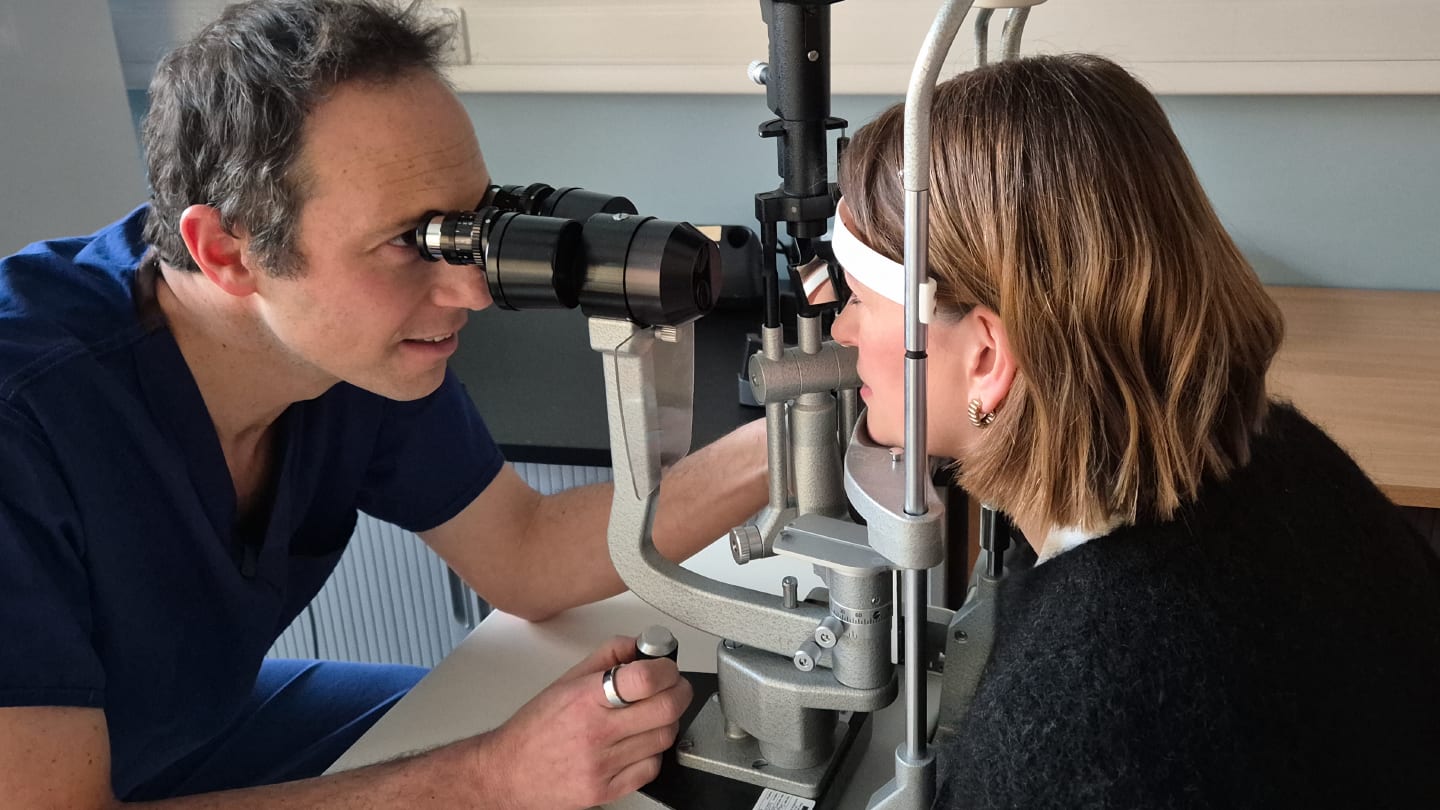

In this interview, Moorfields Hospital consultant ophthalmologist Harry Petrushkina – lead author of a new British Journal of Ophthalmology study reporting visual and anatomical outcomes following intravitreal hydroxypropylmethylcellulose (HPMC) for the treatment of chronic structural hypotony – explains how a flash of insight led him to rethink the problem biomechanically.

From a clinical perspective, what makes hypotony particularly challenging to manage?

Historically, hypotony has been viewed as being on the road toward ocular death – the point at which we stop trying to restore function and instead focus on palliation, ensuring the eye is comfortable and pain free.

When we think about hypotony, we tend to divide it into two domains. The first is acute hypotony, most commonly seen as an immediate postoperative consequence of glaucoma surgery, where there is over-drainage of fluid. The second is hypotony in a very sick eye that is progressively losing vision, where the problem is under-production of fluid due to ciliary body failure. Fundamentally, there are only two reasons for low intraocular pressure: either fluid is leaving the eye too quickly, or the eye is not producing enough fluid.

Acute hypotony following glaucoma surgery or trauma is something we are generally very good at managing. Glaucoma surgeons have been injecting viscoelastic gel into the anterior chamber for decades, and that approach is well established.

The real challenge arises in eyes that gradually depressurize over time. This can occur after multiple retinal detachment surgeries, complex ocular trauma, or longstanding inflammation. In these cases, the ciliary body has effectively stopped working, and we don’t have a good way of replacing that function. Historically, there has been very little that could be done. In many cases, we have either done nothing or injected silicone oil into the eye. Silicone oil doesn’t cure hypotony, but it does provide a scaffold that prevents further collapse of the eye. It’s far from ideal – patients often still have very poor vision through a soft eye filled with silicone oil – but it is sometimes better than no intervention at all.

The breakthrough here wasn’t simply injecting viscoelastic into the eye; people have attempted that for decades. The difference is that it has never been done in a structured way with a clearly defined endpoint. To do something well in medicine, you need to know what you’re aiming for.

What makes this approach different is that we defined the endpoint before starting treatment.

What we found is that once the eye returns to its original length, vision improves, pressure stabilizes, and the eye regains structural integrity. In many patients, treatment can then stop and the eye can simply be observed. Some require top-up treatments, but unlike historical attempts, our outcome metric isn’t just whether the pressure has risen slightly – it’s meaningful visual improvement, and in many cases that improvement has been substantial.

What was the original insight that led your team to explore this therapeutic approach? Was it a flash of inspiration or a more careful consideration over time?

It was definitely a flash of inspiration. Our first patient – the index patient – had already lost vision in her other eye from hypotony. She was young, had a youngfamily, and was hoping to continue driving. Following cataract surgery, her vision had dropped to 1/60. One option was to insert silicone oil, which is what had been done in the fellow eye, but we knew the visual outcome would be poor. Her cornea would likely decompensate, and at best she might achieve 6/60 or 6/36 vision. Alternatively, we could try something different, and the patient was very motivated to explore that option.

At that point, we involved our glaucoma colleagues. In a typical situation, such as an over-draining trabeculectomy, you would inject viscoelastic into the anterior chamber, so that’s what we initially did.

What we then saw on ultrasound was very striking. We could make the anterior chamber absolutely huge, and the intraocular lens from her cataract surgery was moving further and further back as the chamber expanded — but the back of the eye remained extremely soft. On B-scan, the posterior globe didn’t look normally rounded; it looked wavy.

That was the eureka moment. It made us realize that injecting viscoelastic into the anterior chamber wasn’t addressing the underlying problem in chronic hypotony. Instead, we needed to inject into the vitreous cavity and continue injecting until the posterior segment, and the retina, were properly supported and restored to their normal configuration.

We injected once and saw an improvement, then injected again and saw further improvement. We also noticed that with each injection, the axial length was increasing — which makes perfect sense. As we approached the premorbid axial length, as the eye returned to roughly the size it should be, it began to maintain its pressure much more effectively.

Can you talk about the outcome the patient had, and how that has transferred to other patients so far?

There was a very clear governance process around treating that first patient differently. Injecting viscoelastic and leaving it inside the eye is something clinicians have done for a long time, but using it in this way is off-license, so it required appropriate oversight.

When we had this idea, we convened a multidisciplinary team at Moorfields to discuss the case. As with any new approach, it then went through our internal governance processes, including review by the New Technologies Committee. That process is there to ensure the treatment appears safe and sensible and that the patient is fully informed and consented. Initially, permission is granted to treat a single patient and report back, and only then to expand to a small cohort.

Once approved, we treated the first patient and the outcome was remarkable. Her vision improved from counting fingers – effectively off the top of the Snellen chart – to 6/9 at one point, and she is now around 6/12. To go from 1/60 to 6/12 is an extraordinary result, better than what you might expect from very good cataract surgery.

Based on that outcome, we were given permission to treat additional patients. The paper reports on the first eight patients at one year following treatment and examines how they did overall.

We deliberately chose a one-year time point because this is a marathon, not a sprint. Simply showing that the pressure is 10 immediately after an injection isn’t very meaningful. What matters is whether the effect is sustained and whether patients do well over the medium to long term. Hopefully, the results reassure both clinicians and patients that this approach doesn’t just produce a transient improvement, but delivers meaningful, durable outcomes at one year.

What are the next steps for you in this line of research?

This is really promising, but it's early data. There are several things lined up. We currently have a epidemiology study ongoing. One of the big problems is that people don't diagnose hypotony because there's “nothing we can do about it.” Actually a huge number of eyes are hypotonous, but it never gets a SNOMED code, so we can never really diagnose it or get a sense of the epidemiology.

There is a new national study through the British Ophthalmological Surveillance Unit (BOSU) into chronic ocular hypotony, and the next thing is to engage colleagues all over the UK to create a network where we can run a National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) study looking at treatment versus no treatment, to basically prove what we've proved but on a much greater scale.

The next thing would be to understand what is the best gel to use. HPMC is the gel we’ve been using for a long time because it's safe and we know how it works. But we need to start doing head-to-head trials, looking at different gels, cohesive, dispersive, different levels of cross-linking, different concentrations of hyaluronic acid, etc.

For ophthalmologists encountering hypotony in practice, what message would you want them to take away from this study?

There are two key messages. The first is that I want people to seriously question the point at which we give up. This idea of the pre-phthisical or phthisical eye as the stage where we stop thinking, give topical steroids and cycloplegia, and essentially disengage from active management is something that really bothers me.

As a uveitis specialist, I look after children, young adults, and adults with ocular inflammation. Historically, there has always been a group of these patients who progress down this path, often because inflammation wasn’t managed aggressively enough earlier on. The idea that I might work hard to preserve a child’s eye for the first 15 years of their life, only to accept that it will eventually lose vision because of low pressure, has always felt completely unacceptable to me. Yet there has been remarkably little robust research into hypotony, and almost none that seriously considers the biomechanics of what happens when the eye begins to depressurize.

One of the most important aspects of this project has been early collaboration with bioengineers at UCL. We’ve been modelling soft eyes and working with ex vivo pig eyes to understand how the viscoelastic properties of the cornea, sclera, and vitreous interact when the eye becomes hypotonous. We talk about low intraocular pressure as though it’s something we can measure accurately, but in reality it isn’t. Almost all of our equipment is designed for glaucoma, not hypotony, and once the eye softens, the biomechanical assumptions behind those measurements fall apart.

That leads to my second takeaway: we should be using axial length far more widely in hypotony. It’s a simple, readily available measurement. If the eye is getting shorter, you are clearly not winning. A pressure reading of 4mmHg instead of 3mmHg isn’t reassuring — it’s often just noise. Measuring whether the eye is shrinking is, in my view, a far more meaningful and reliable metric in these patients.